Dr. Lev Centrih

Dr. Nataša Henig Miščič

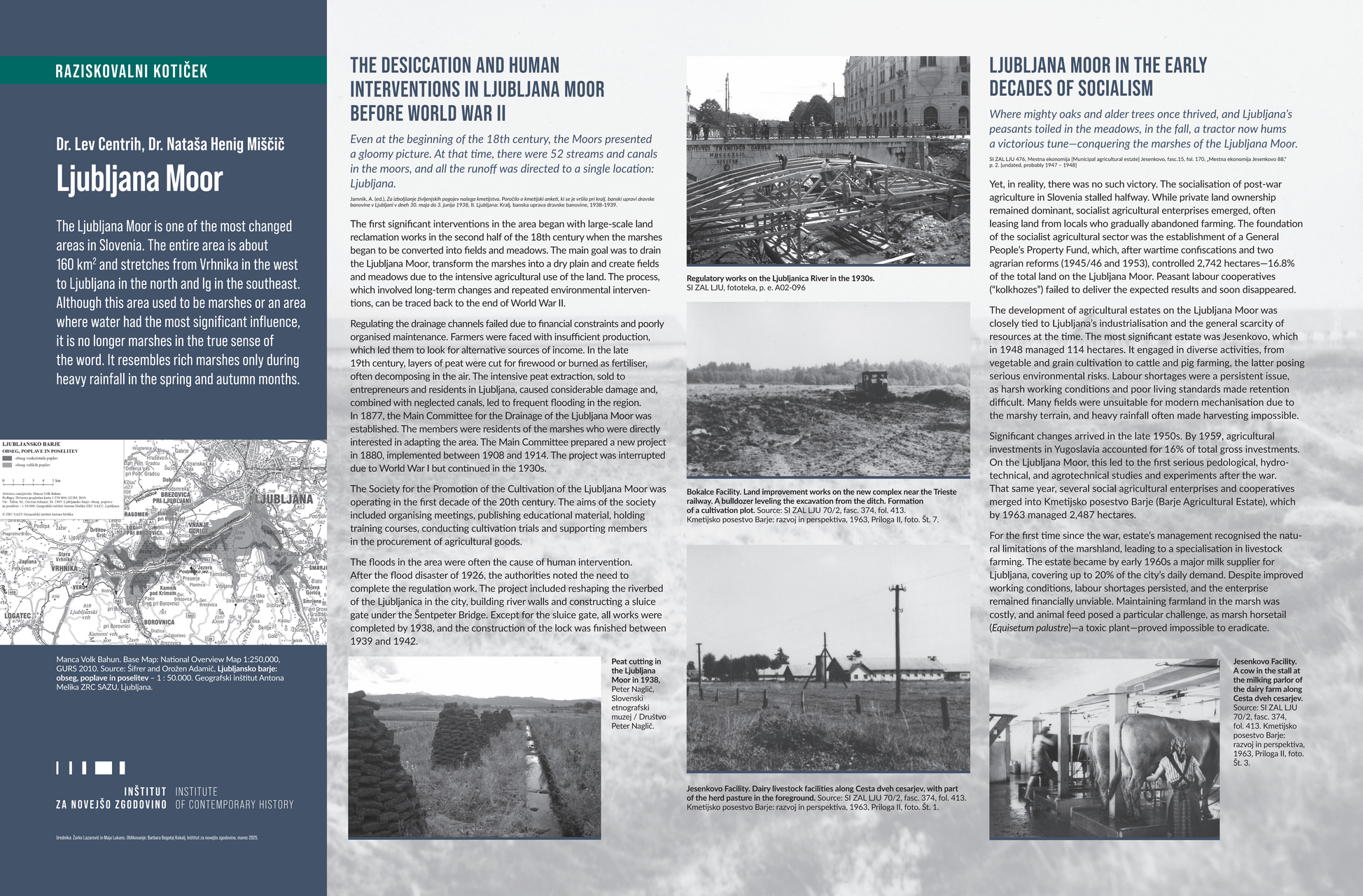

The Ljubljana Moor is one of the most changed areas in Slovenia. The entire area is about 160 km2 and stretches from Vrhnika in the west to Ljubljana in the north and Ig in the southeast. Although this area used to be marshes or an area where water had the most significant influence, it is no longer marshes in the true sense of the word. It resembles rich marshes only during heavy rainfall in the spring and autumn months.

Manca Volk Bahun. Base Map: National Overview Map 1:250,000, GURS 2010. Source: Šifrer and Orožen Adamič, Ljubljansko barje: obseg, poplave in poselitev – 1 : 50.000. Geografski inštitut Antona Melika ZRC SAZU, Ljubljana.

THE DESICCATION AND HUMAN INTERVENTIONS IN LJUBLJANA MOOR BEFORE WORLD WAR II

Even at the beginning of the 18th century, the Moors presented a gloomy picture. At that time, there were 52 streams and canals in the moors, and all the runoff was directed to a single location: Ljubljana.

The first significant interventions in the area began with large-scale land reclamation works in the second half of the 18th century when the marshes began to be converted into fields and meadows. The main goal was to drain the Ljubljana Moor, transform the marshes into a dry plain and create fields and meadows due to the intensive agricultural use of the land. The process, which involved long-term changes and repeated environmental interventions, can be traced back to the end of World War II.

Regulating the drainage channels failed due to financial constraints and poorly organised maintenance. Farmers were faced with insufficient production, which led them to look for alternative sources of income. In the late 19th century, layers of peat were cut for firewood or burned as fertiliser, often decomposing in the air. The intensive peat extraction, sold to entrepreneurs and residents in Ljubljana, caused considerable damage and, combined with neglected canals, led to frequent flooding in the region. In 1877, the Main Committee for the Drainage of the Ljubljana Moor was established. The members were residents of the marshes who were directly interested in adapting the area. The Main Committee prepared a new project in 1880, implemented between 1908 and 1914. The project was interrupted due to World War I but continued in the 1930s.

The Society for the Promotion of the Cultivation of the Ljubljana Moor was operating in the first decade of the 20th century. The aims of the society included organising meetings, publishing educational material, holding training courses, conducting cultivation trials and supporting members in the procurement of agricultural goods.

The floods in the area were often the cause of human intervention. After the flood disaster of 1926, the authorities noted the need to complete the regulation work. The project included reshaping the riverbed of the Ljubljanica in the city, building river walls and constructing a sluice gate under the Šentpeter Bridge. Except for the sluice gate, all works were completed by 1938, and the construction of the lock was finished between 1939 and 1942.

Peat cutting in the Ljubljana Moor in 1938, Peter Naglič, Slovenski etnografski muzej / Društvo Peter Naglič.

Regulatory works on the Ljubljanica River in the 1930s. SI ZAL LJU, fototeka, p. e. A02-096

Bokalce Facility. Land improvement works on the new complex near the Trieste railway. A bulldozer leveling the excavation from the ditch. Formation of a cultivation plot. Source: SI ZAL LJU 70/2, fasc. 374, fol. 413. Kmetijsko posestvo Barje: razvoj in perspektiva, 1963, Priloga II, foto. Št. 7.

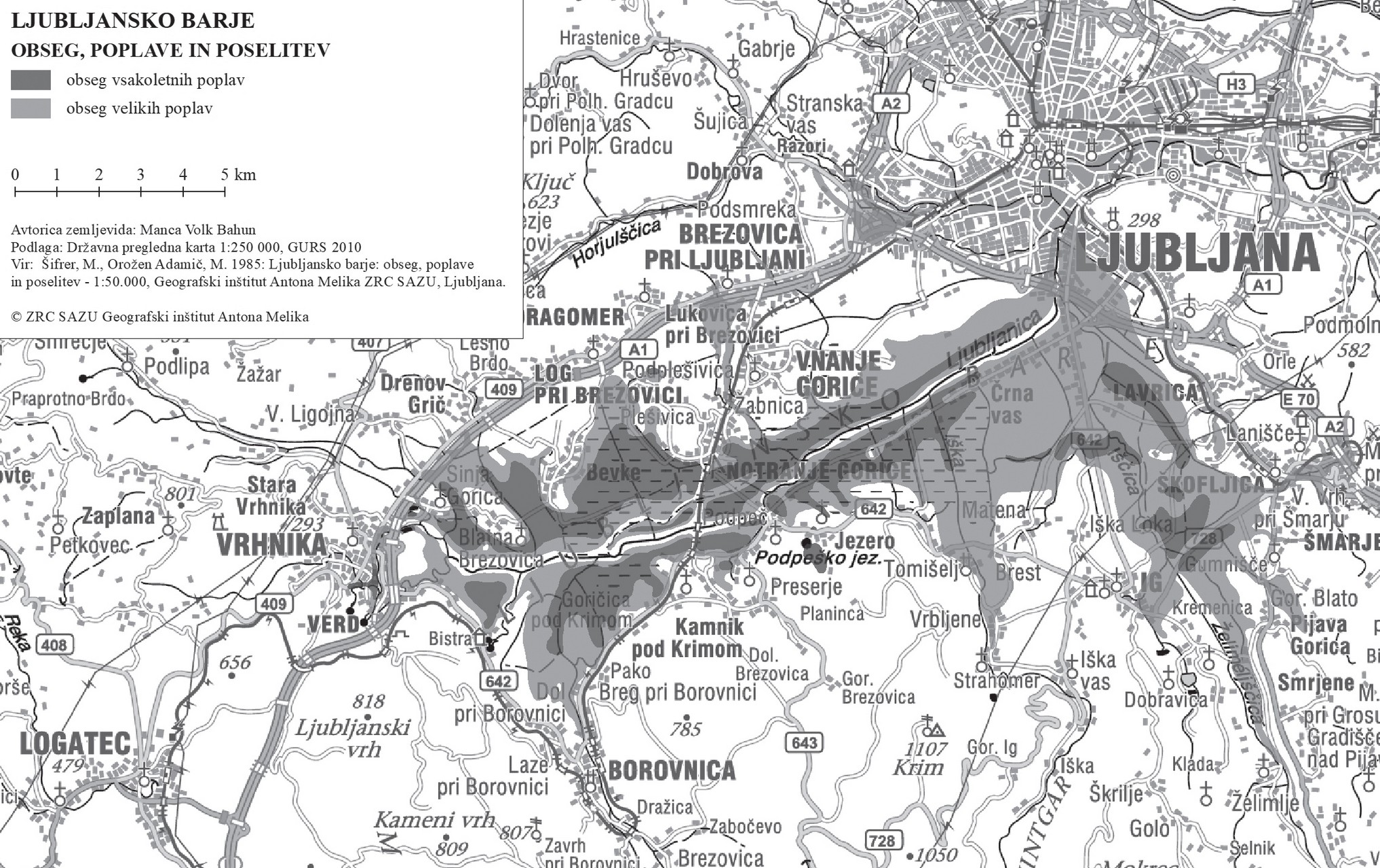

Jesenkovo Facility. Dairy livestock facilities along Cesta dveh cesarjev, with part of the herd pasture in the foreground. Source: SI ZAL LJU 70/2, fasc. 374, fol. 413. Kmetijsko posestvo Barje: razvoj in perspektiva, 1963, Priloga II, foto. Št. 1.

LJUBLJANA MOOR IN THE EARLY DECADES OF SOCIALISM

Where mighty oaks and alder trees once thrived, and Ljubljana’s peasants toiled in the meadows, in the fall, a tractor now hums a victorious tune—conquering the marshes of the Ljubljana Moor.(SI ZAL LJU 476, Mestna ekonomija [Municipal agricultural estate] Jesenkovo, fasc.15, fol. 170, „Mestna ekonomija Jesenkovo 88,“ p. 2. [undated, probably 1947 – 1948])

Yet, in reality, there was no such victory. The socialisation of post-war agriculture in Slovenia stalled halfway. While private land ownership remained dominant, socialist agricultural enterprises emerged, often leasing land from locals who gradually abandoned farming. The foundation of the socialist agricultural sector was the establishment of a General People’s Property Fund, which, after wartime confiscations and two agrarian reforms (1945/46 and 1953), controlled 2,742 hectares—16.8% of the total land on the Ljubljana Moor. Peasant labour cooperatives (“kolkhozes”) failed to deliver the expected results and soon disappeared.

The development of agricultural estates on the Ljubljana Moor was closely tied to Ljubljana’s industrialisation and the general scarcity of resources at the time. The most significant estate was Jesenkovo, which in 1948 managed 114 hectares. It engaged in diverse activities, from vegetable and grain cultivation to cattle and pig farming, the latter posing serious environmental risks. Labour shortages were a persistent issue, as harsh working conditions and poor living standards made retention difficult. Many fields were unsuitable for modern mechanisation due to the marshy terrain, and heavy rainfall often made harvesting impossible.

Significant changes arrived in the late 1950s. By 1959, agricultural investments in Yugoslavia accounted for 16% of total gross investments. On the Ljubljana Moor, this led to the first serious pedological, hydrotechnical, and agrotechnical studies and experiments after the war. That same year, several social agricultural enterprises and cooperatives merged into Kmetijsko posestvo Barje (Barje Agricultural Estate), which by 1963 managed 2,487 hectares.

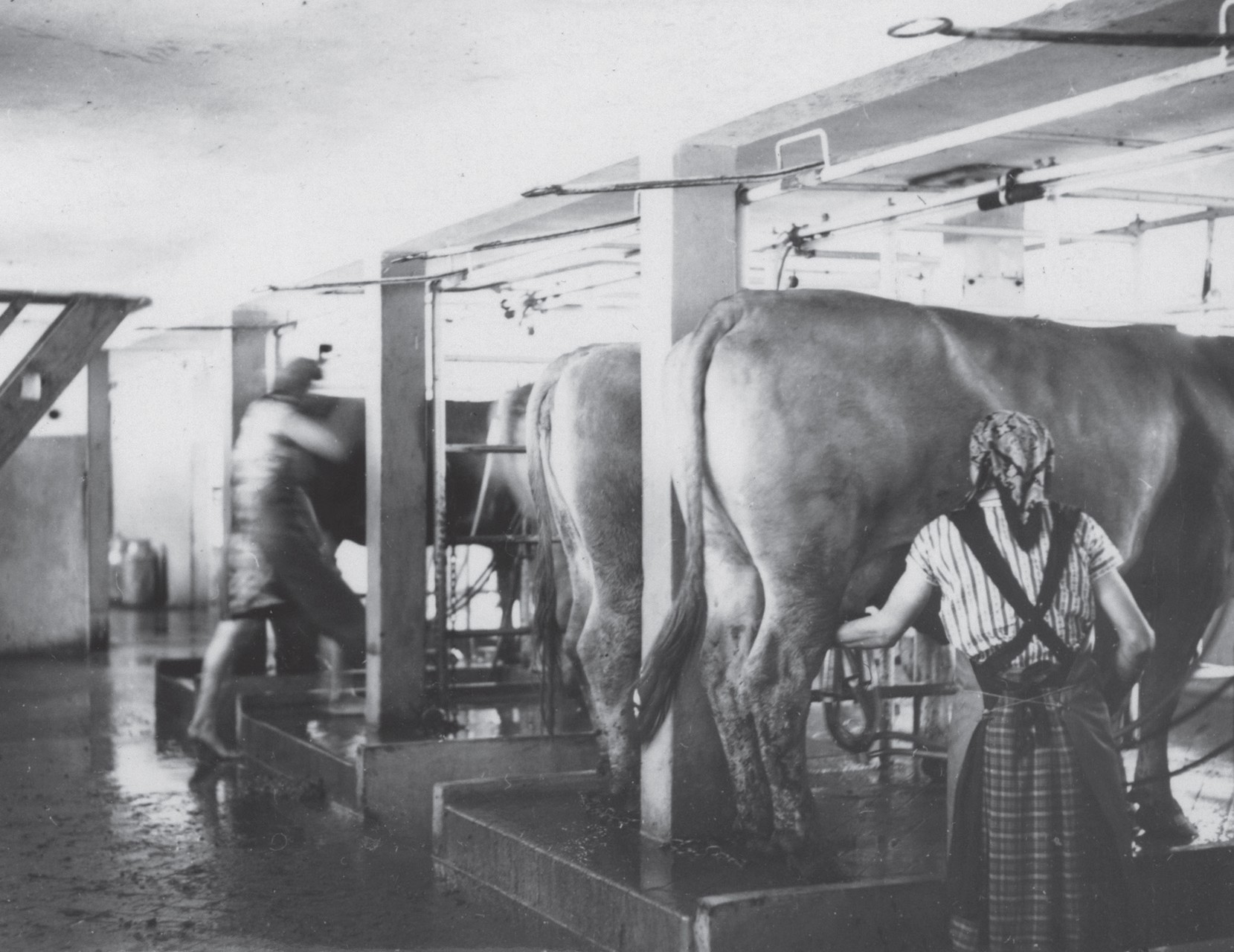

For the first time since the war, estate’s management recognised the natural limitations of the marshland, leading to a specialisation in livestock farming. The estate became by early 1960s a major milk supplier for Ljubljana, covering up to 20% of the city’s daily demand. Despite improved working conditions, labour shortages persisted, and the enterprise remained financially unviable. Maintaining farmland in the marsh was costly, and animal feed posed a particular challenge, as marsh horsetail (Equisetum palustre)—a toxic plant—proved impossible to eradicate.

Jesenkovo Facility. A cow in the stall at the milking parlor of the dairy farm along Cesta dveh cesarjev. Source: SI ZAL LJU 70/2, fasc. 374, fol. 413. Kmetijsko posestvo Barje: razvoj in perspektiva, 1963, Priloga II, foto. Št. 3.

***