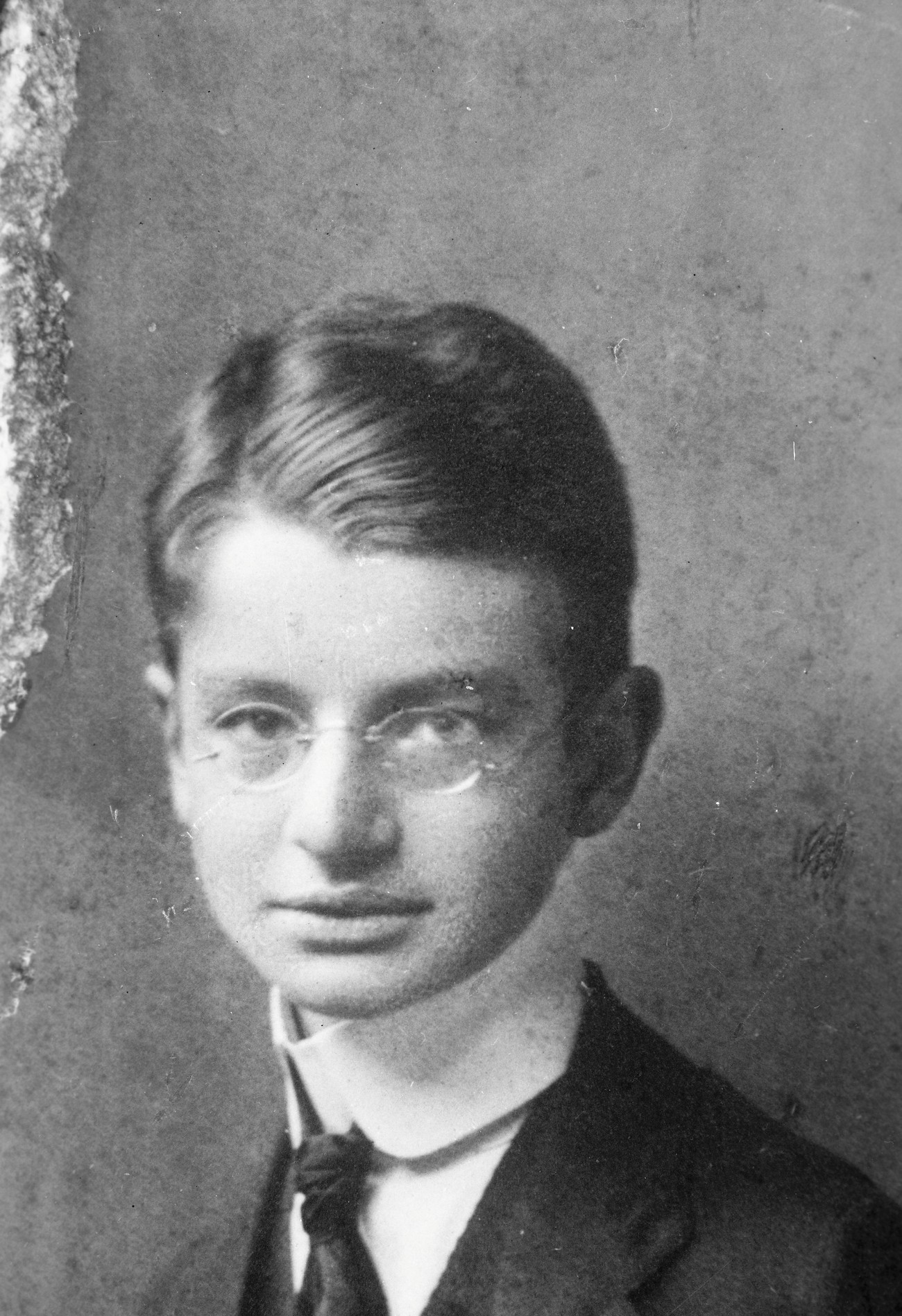

FRAN ZWITTER, historian, Dean of the Faculty of Arts, and Rector of the University of Ljubljana (1929)

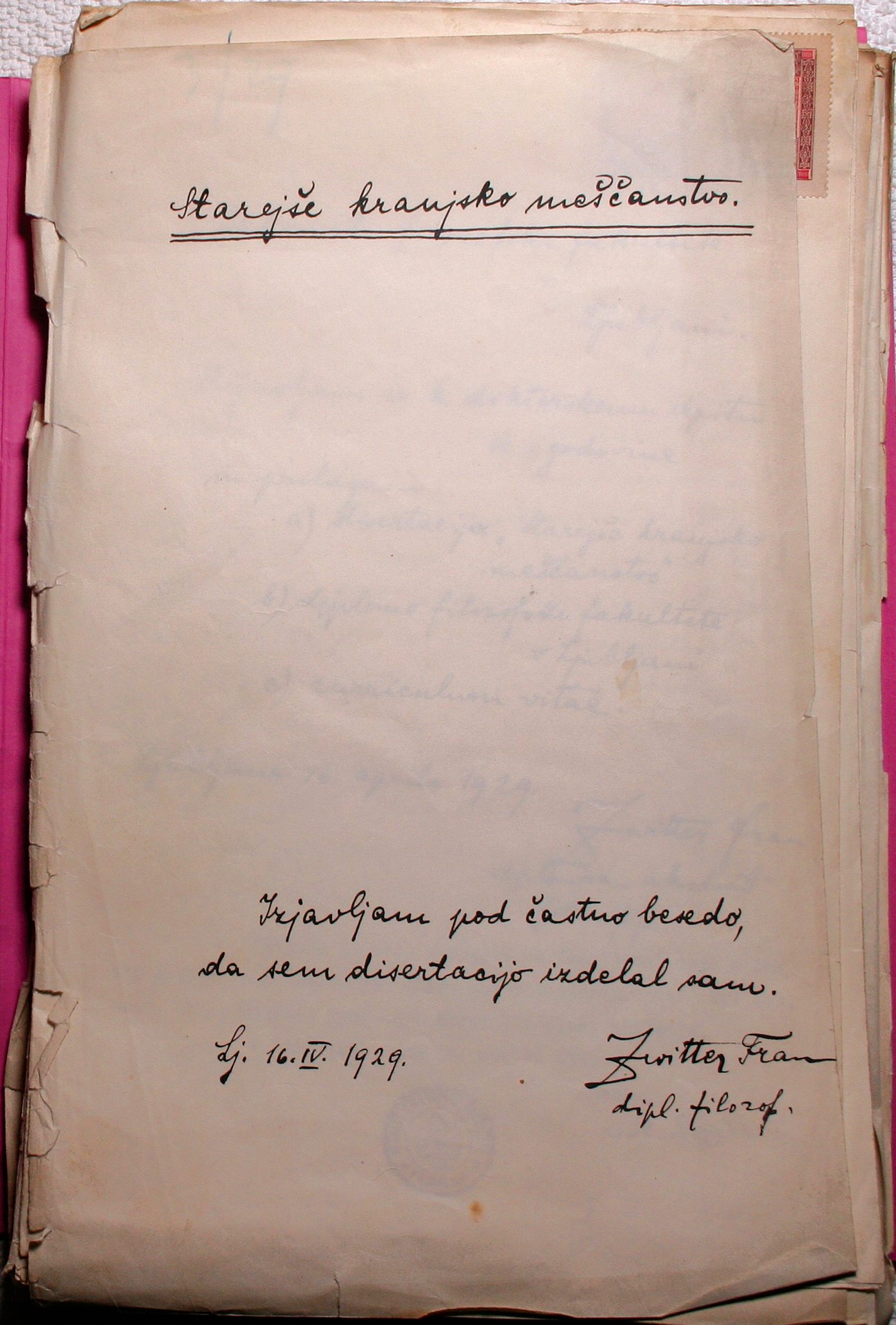

Older citizenry of Kranj. Mentor: Milko Kos. Promotion: November 13, 1929

From 1937, he lectured at the Department of History. He was interned in Aprico during the war and joined the Partisans where he assumed the leadership of the Scientific Institute under SNOS in 1944. After the war, he worked at Foreign Ministry in Beograd until 1948 as an expert on border issues before he returned to the faculty where he lectured until his retirement. He was, among other things, a Rector (1952/1954) and a Vice-chancellor (1954/1956) of the University of Ljubljana, and a full member of SAZU. His research field was social history, history of cities, and the national political issues.

Fran Zwitter as a schoolboy before departing for Vienna. Source: Museum of Contemporary History Slovenia.

Fran Zwitter with his wife Majda and six of the eight grandchildren. Source: Museum of Contemporary History of Slovenia.

Front page of the dissertation manuscript of Fran Zwitter. Source: Archive of the Faculty of Arts, soctorate folder of Fran Zwitter.

Žiga Zwitter, historian and grandson:

In accordance with the contemporary chronological orientation of the Historical Seminar, the predecessor of the current Department of History, the emphasis in the dissertation is on the Middle Ages, although he also worked with modern sources. His main mentor, Milko Kos, was also a medievalist. His dissertation was influenced by his studies in Ljubljana and Vienna. Viennese influence is also evident in the fact that his mentor, Alfons Dopsch, was available for advice. This influence is reflected in the substantive emphasis, with the legal history being strongly represented in the treatment of medieval towns and citizens in Carniola. He also discussed the political and economic history of said settlements. If we compare this to his later treatises on the same subject, we can safely say that he was strongly influenced by postdoctoral training in Paris. His later concept of writing about medieval cities in Slovenia was broader, his social history more strongly represented, and during his studies in France, he became even more aware of the international literature. His dissertation, for example, does not consider the fundamental work on the history of the medieval cities of the Belgian historian Henri Pirenn, even though it was written before the dissertation. He did take them into account in his later discussions, which were acknowledged in the publications of Milko Kos and Bogo Grafenauer. If we evaluate the dissertation in the contemporary context, we can certainly conclude it is an extremely thorough work. This is all the more evident if we compare it with five doctoral theses in geography at the University of Vienna between 1900 and 1918; like I did recently. It is clear that the coeval expectations of doctoral dissertations were quite similar to what we today expect from the master's work within the Bologna system. A large number of new results and a good conceptualization with foreign literature was just something that was desirable, but not mandatory. With Grandpa, however, that is certainly well developed.Tomaž Zwitter, son and astrophysicist:

I am the youngest son of Fran Zwitter, born when he was 56; no doubt a "Benjamin". Despite the age difference, my father was extremely influential. I work in the field of astrophysics and I teach at the Faculty of Mathematics and Physics. And yet: he influenced my worldview where all facts need to be evaluated with one's own head, based on facts and sources; and that there is nothing wrong by moving boundaries if you manage to do that from time to time. An upright, independent and moral perspective on science, teaching and working with students. I believe that I, in my humble capacity, match his attempts to make students think with their own heads and contribute something to the whole society.Matevž Dular, grandson, and professor of mechanical engineering:

Grandpa never really took the time for me because, as I recall, he was always busy. I came to his apartment straight from school every day and waited for my parents to pick me up. He was always in a suit, which is something I didn't adopt. What I did inherit from him is drinking coffee and an even more messy desk. We didn't go on trips. The only one I recall is the one to Bela cerkev (probably on November 1), which we always did. When I was in elementary school, we played chess, but I don't know whether he let me win or not. He did not, however, allow himself to have a piece less at the beginning. We also played tarot with very strict rules. All points were counted, no rounding up.Matjaž Zwitter, son and oncologist:

I am the eldest son of Fran Zwitter, a doctor by profession. I'm retired, but I still teach medical ethics and law at the University of Maribor. I owe my father insatiable curiosity about all the world issues. I try to be as broad as possible. Our society does not always condone if you write about things outside your area of interest. Such was our father, and such are his children.Anja Dular, daughter, librarian and archeologist:

I studied archaeology before I ended up among old books. I focused on old prints at the National Museum, which is known as "book archaeology" in modern historiography. Neither by methodology nor by material did I stray far from my profession, except I'm dealing with books instead of artifacts. All three children of Fran Zwitter went their own paths, all the result of conversations with him. He allowed us plenty of freedom to think. He never directed us and he was always ready to talk about anything. When I decided on archaeology, he was very pleased. He supported me and when I decided to do my diploma thesis in Vienna, he paid my stay there. He said that what I would get from the academy would not cover my expenses. He probably remembered his student days.