The Philosophical Trinity: SLAVOJ ŽIŽEK, philosopher (1981)

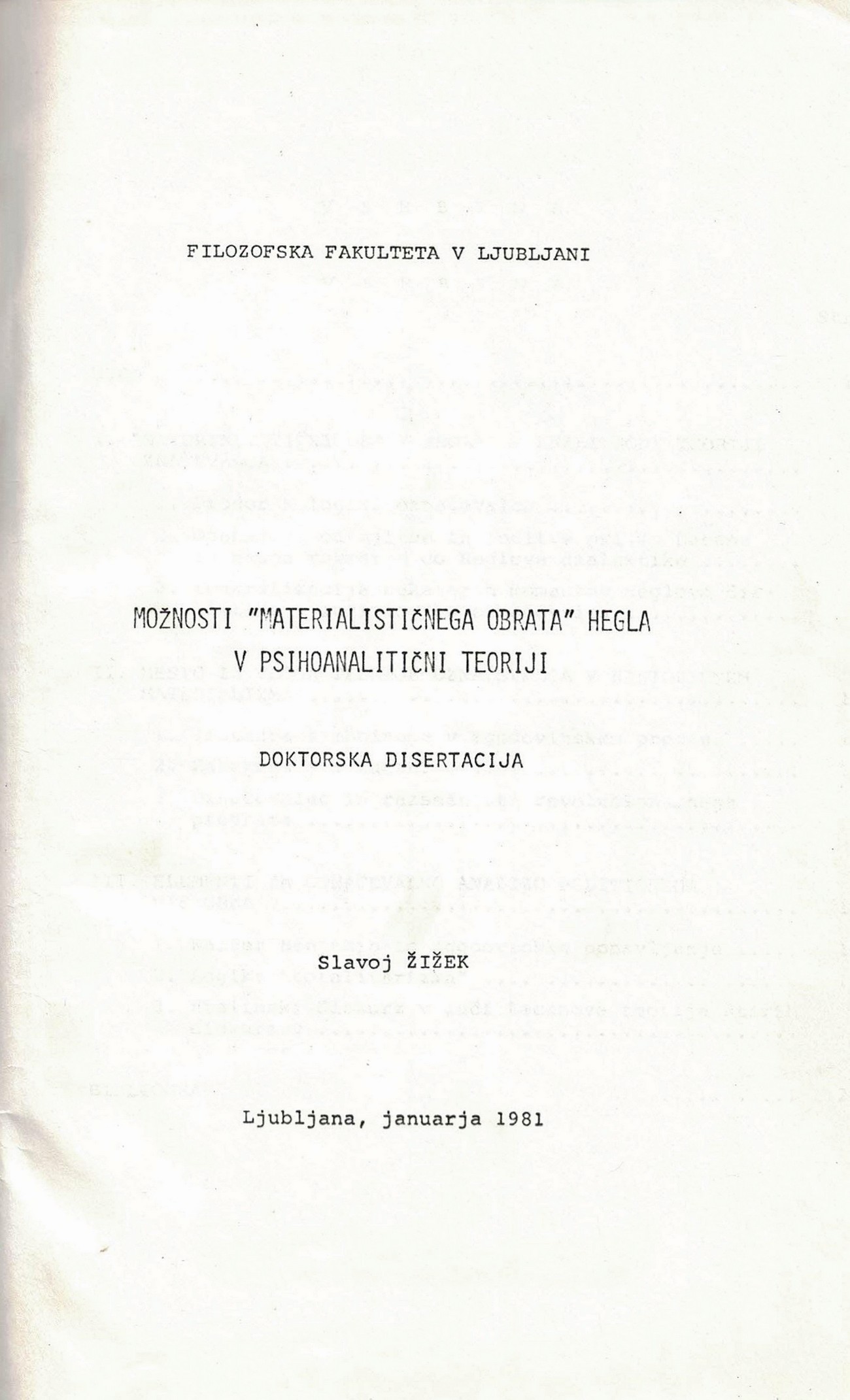

Possibilities of Hegel's "materialist turn" in the psychoanalysis theory. Mentor: Božidar Debenjak. Promotion: June 30, 1981

He received his first Ph.D. from the Faculty of Arts in 1981, and and the second Ph.D. in 1985 at the University at the University of Paris VII under Jacques-Alain Miller in psychoanalysis. In the Eighties, he was socially and politically active in the Slovenian territory. He works as a researcher at the Faculty of Arts, and as a full-time or visiting professor at various world-renowned universities. His research spans from German Idealism to psychoanalysis, political philosophy, and numerous other topics. He is a leading member of the Ljubljana Lacanian School of Philosophy, together with Mladen Dolar and Alenka Zupančič.

Author: Uroš Abram. Source: Mladina

The cover of Slavoj Žižek's dissertation

Mladen Dolar, philosopher:

Slavoj Žižek's Ph.D. should have a special place at the exhibition of PhDs, considering he is by far the most famous Ph.D. candidate at the Faculty of Arts. He lectures at all world universities and has published numerous books translated into 30 languages. Many books deal with his work, too. Slavoj did not give an interview, which may be interpreted as arrogance, but he has good reasons. I was present in 1975 when he submitted his master's degree in French structuralism. It was rejected, which was unusual for those times. He was not turned down for professional reasons, but quite the opposite: the commission assessed that the dissertation was brilliant. He was rejected solely for political reasons, namely his inappropriate attitude towards Marxism. The commission asked for an appendix with a clarification. When he wrote it, they barely let him pass after he went through an utterly humiliating defense. He was an intern at the Department of Philosophy at the time, and it was both agreed and expected that he would be hired there. Due to the master's degree incident, the promise was broken, and he ended up on the street overnight. Not many people were unemployed at the time, but somehow Slavoj Žižek ended up in this situation. That is certainly a stain on the Faculty of Arts, which can be proud of many achievements, but the centenary is also an opportunity for reflection and acknowledgment of injustices that have occurred. There were others, but this one is significant because of the status Slavoj achieved after that. He was offered the world in the 1990s, but he was already engaged elsewhere worldwide. It is telling that Slavoj Žižek never lectured at the Faculty of Arts, except for a part-time stint in one semester.

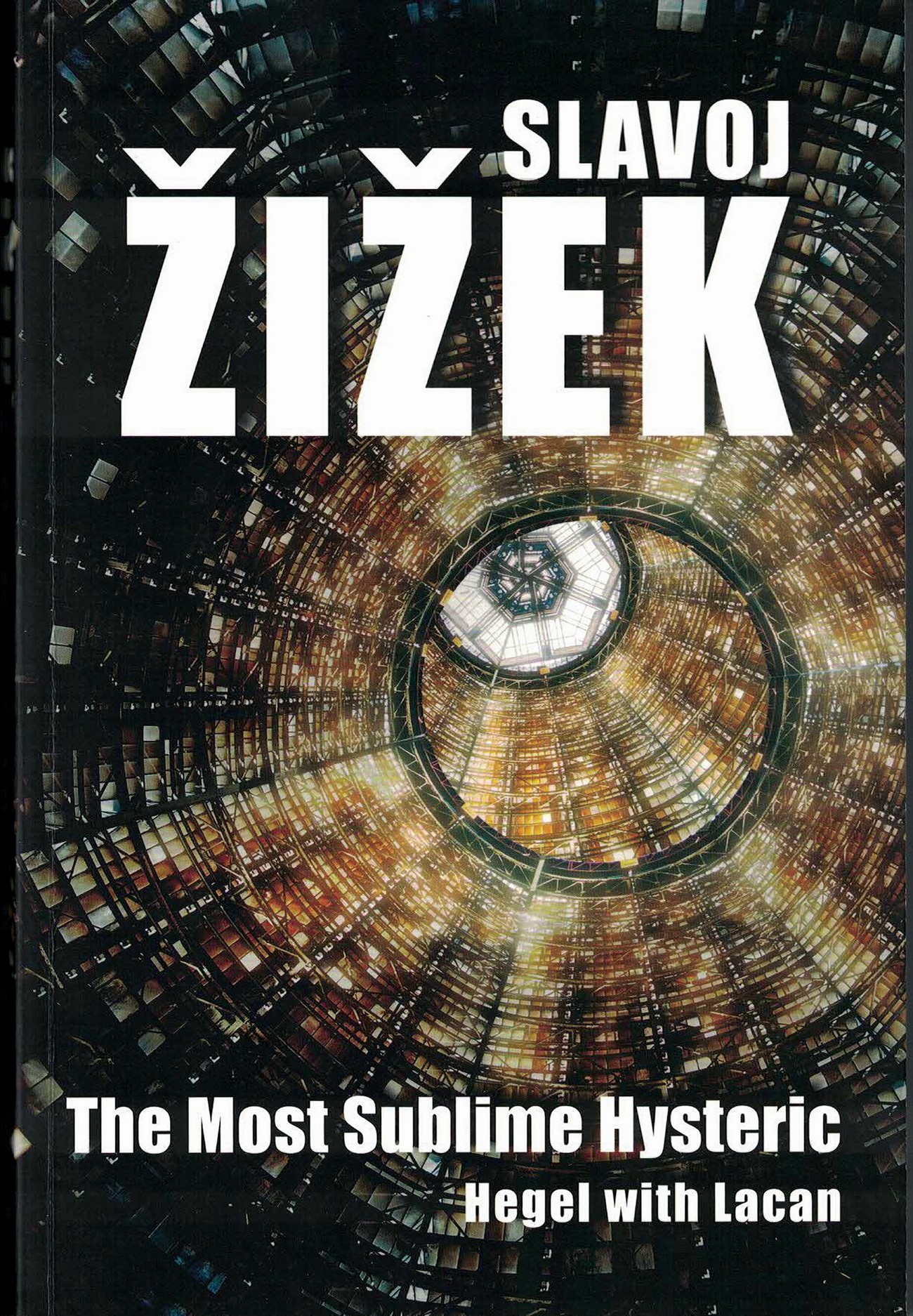

The cover of Žižek's book The Most Sublime Hysteric, which is based on the dissertation he defended in Paris.

Why do you believe Yugoslav self-management helped me in my career? It is true, that without the communist pressures, I would be an old, retired and completely unknown professor of philosophy in Ljubljana these days. I will forever be grateful to the Yugoslav Communists for two things. First, for keeping the borders open and enabling me to travel abroad and stay up-to-date with current affairs. The other best thing that happened to me was Tito's letter in the early 1970s when he tyrannically decided what can and what cannot be done in the state. I felt that as I could not get a job for years. On the other hand, it was a small miracle, since I established contacts in the West whilst I was unemployed. I admit that without these pressures in the dark Seventies, I would be a nobody from Ljubljana. The situation was very cynical. (Slavoj Žižek, philosopher. From the interview with Srečko Horvat, Mladina, 2019, volume XI/6).